Paper or digital? Ever since electronic medical records became a possibility, practices everywhere have been asking this question. If you happen to be in one of those practices, we can help.

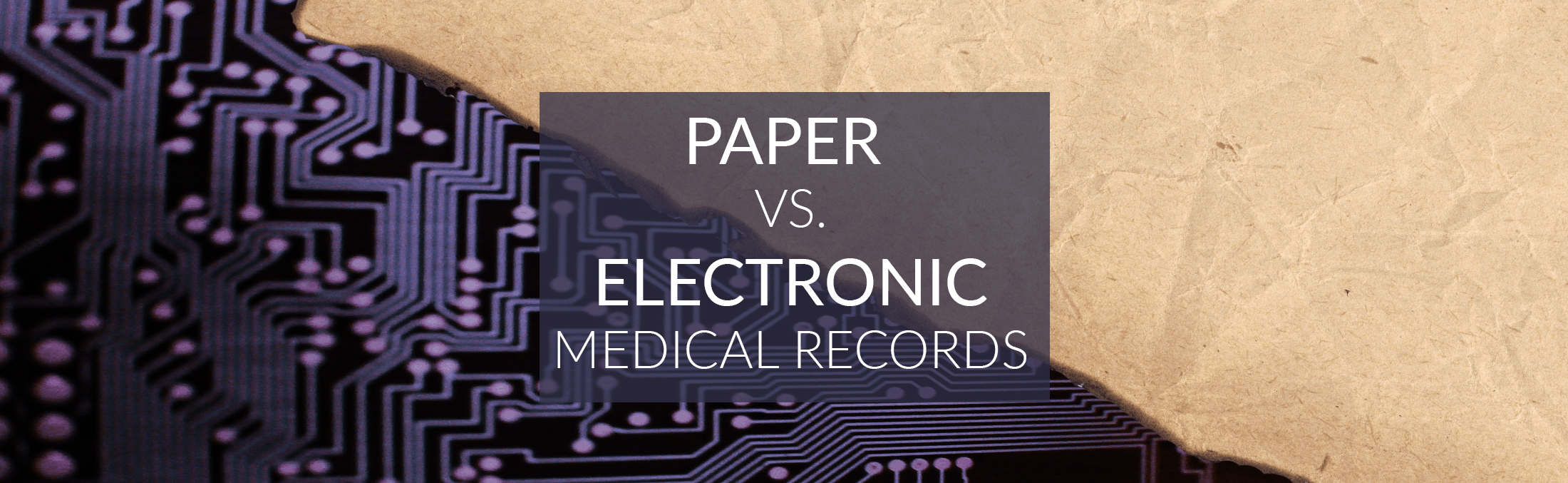

Here we have actually measured the merits and weaknesses of paper vs. digital medical documentation. The chart below gives you a quick rundown of our findings. Want to find out more about each category and how we got each answer? Just scroll past the chart and click on the appropriate tab.

So how did we get these results? Well, take a look at these reasons:

The short answer: Digital wins by a mile.

The long answer: The reasons for Digital’s superiority in this area are apparent.

First, computers cut out the manual processes of seeking a record and retrieving it. All of those things take significantly more time and effort with paper. That can make all the difference in situations where emergency access to a patient’s records is necessary.

Second, physical distance between the person accessing the record and its storage location are no longer concerns with digital records. For example, a person can access a file on the cloud wherever he may be in the world, provided he has a Web connection.

Finally, concurrent access to the same file is rendered possible by digital technology. With paper records, you usually have only one copy of a medical file at a practice. If one person is already using that file, no one else can—unless they are working digitally. Cloud technology would help sync alterations, for instance.

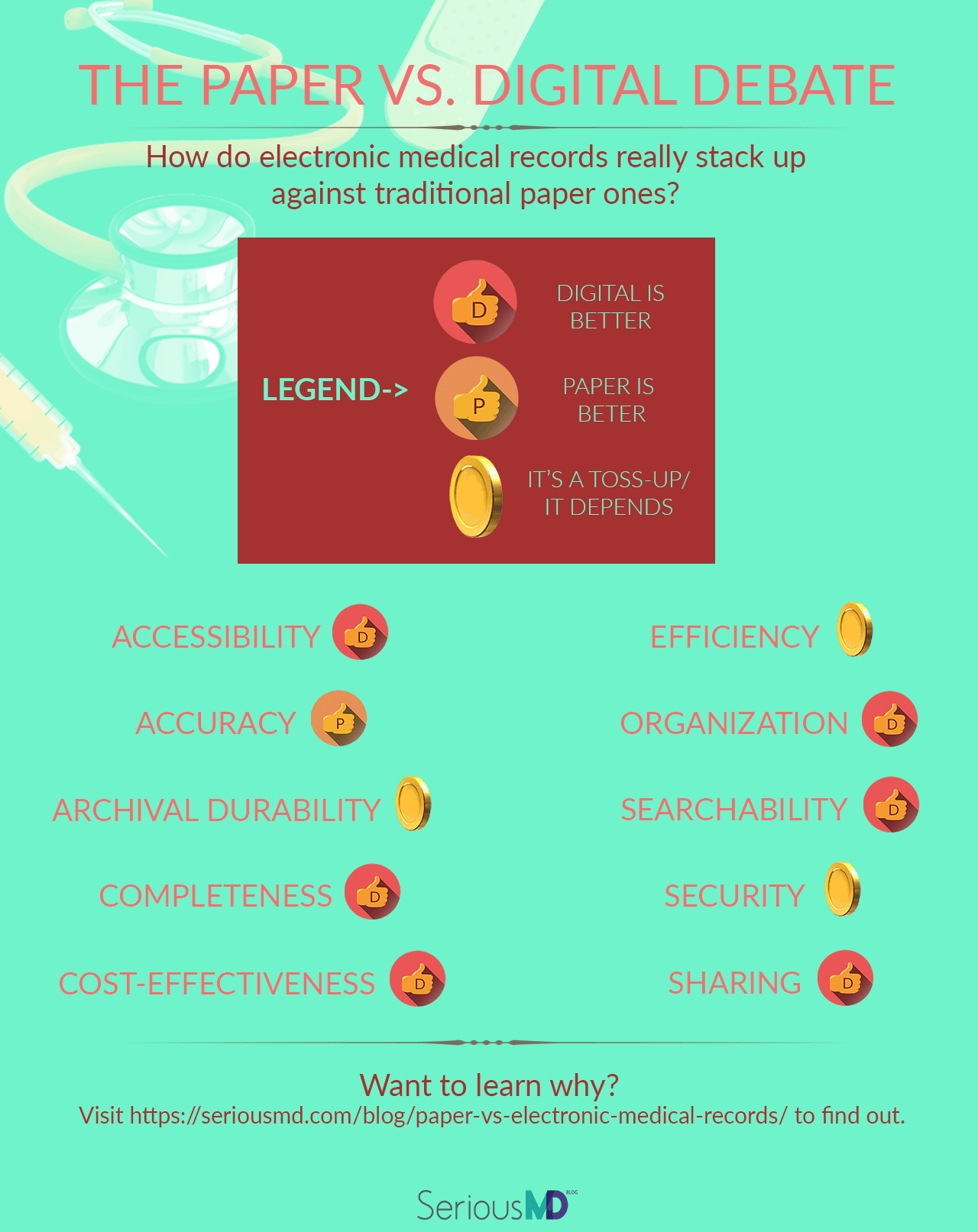

SeriousMD itself permits both manual and automated syncing of record data, to keep files constantly updated even with multi-user access.

We should note that there are some specific situations where Paper would win over Digital in the accessibility debate. Format mismatches between the storage source of a digital record and the terminal being used to access it would be an example. Even format obsolescence might be a risk in the future.

In such cases, paper’s agnostic character—the fact that it can be read without requiring a particular program or computing system to access it—would make it preferable.

The short answer: Paper wins—but largely because of human laziness/ineptitude.

The long answer: On the face of it, one might expect an EHR to win over a physical medical record here. It is likely to be more complete, for one thing, and also boasts more exhaustive charting and form options.

However, digital medical records actually tend to be less accurate than paper ones. Electronic records were found to have a 24.4% documentation error rate in a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. By contrast, paper medical records had a 4.4% error rate in the same study.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Siddhartha Yadav, suggested that the difference could be due to the time gap between examination and documentation for some physicians. These doctors might go in, do their rounds, and then attempt to create the electronic record later from memory.

Were the same doctors using paper, they would be more likely to create the record at or immediately after examination. That would mean fewer chances of their memories failing them.

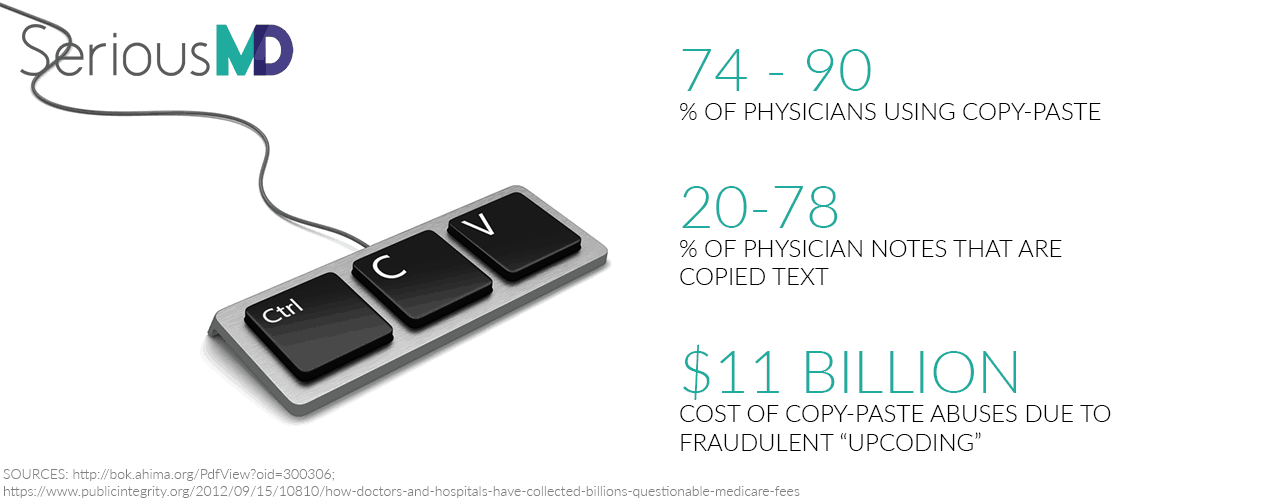

Yadav also suggested that another, even likelier cause for the errors is the Copy-Paste Problem. This issue has been acknowledged more than once already as a snag for EHRs. Among other things, it has also been noted as a potential vehicle for medical fraud.

This is through “upcoding”, the process of over-reporting (often through copy-paste) medical procedures on a patient’s record. These basically fictional procedures reflect as real ones in the patient’s billing statement if not detected for what they are.

The use of copy-paste to clone data from one field of a medical record to another is obviously intended to save time. The trouble arises when medicos become too lazy to check that all the cloned data is still applicable. Changes to a patient’s condition would require editing that information, after all—but some are simply too lazy (or too invested, billing-wise) to care.

Examples of complications from copy-paste issues include a case where a patient was mistakenly portrayed as having a history of breast cancer as opposed to a family history of the ailment. Because this did not agree with her insurance data, she nearly lost her coverage. All because someone in a hospital was too lazy to ensure proper documentation.

This hardly means the copy-paste function should be removed from EHRs, of course. It is a function highly susceptible to abuse, yes. Yet, retrograding technology instead of moving it forward seems an odd answer at any time.

Rather, healthcare professionals should be trained better and informed of the dangers of copy-pasting. At the same time, ongoing performance evaluations and feedback loops may be necessary to monitor record accuracy.

It is suggestive, for instance, that the JAMA article mentioned above found the documentation error rates for resident physicians to be 1/3 of that for attending physicians. Yadev’s proposed explanations were the relative techno-savviness of the younger residents and the fact that they are typically under more scrutiny than their better-established colleagues.

Given better training and more incentive to be accurate, other healthcare workers would likely see reduced error rates too.

The short answer: Paper can last longer, in and of itself. However, digital records can be copied more easily, which gives them better survival chances out of redundancy.

The long answer: This is a toss-up. Technically, good-quality paper records kept in a safe, almost-hermetically-sealed location have the potential to outlast digital ones kept in a single drive or magnetic tape array.

This is since digital media storage wears out. Backblaze, for example, puts the median lifespan for hard drives at 6 years. A CD or DVD will have about 5 to 10 years. Magnetic tapes have anywhere from 10 to 30 years. Flash storage degrades based on write cycles instead of age, on the other hand, but regular use would see most getting about 5 to 10 years off a flash drive as well.

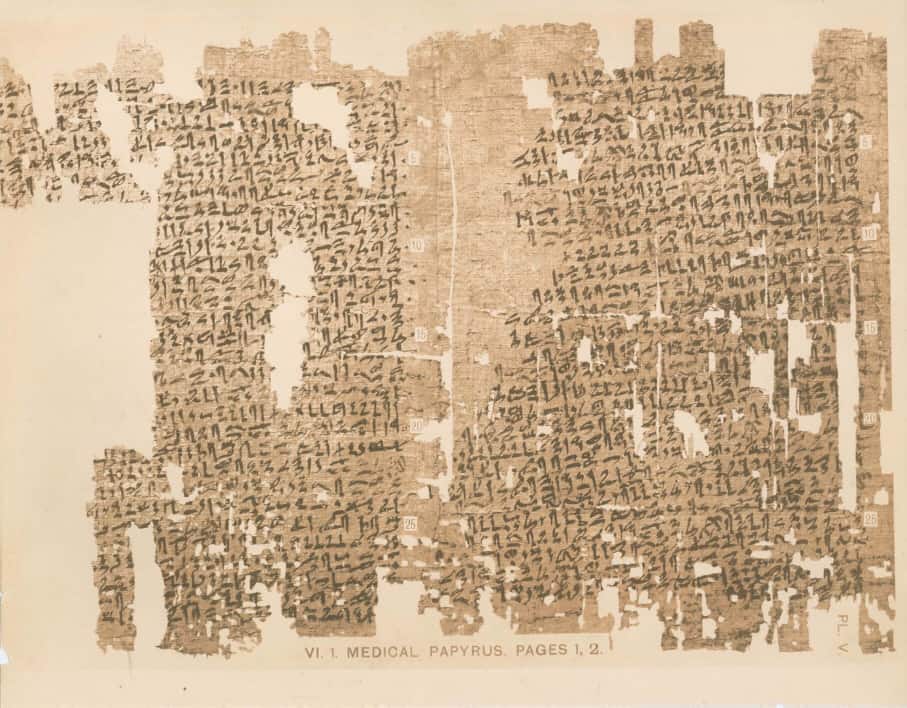

On the other hand, the oldest discovered medical text, the Kahun Medical Papyrus, is still extant (albeit with some natural wear and tear) after its creation c. 1800 BCE.

The Kahun Medical Papyrus is a fine example of the longevity paper documents can boast.

A persistent concern too for digital records has to do with vendor endurance. There are occasions when the vendor/maker of a particular EHR ceases support for the product. Some companies even cease to exist, with similar results for their products.

When this happens, you are stuck with an EMR program that will no longer keep up with industry needs and regulations. The only thing to do then is to switch to an entirely different EHR.

How can you avoid this scenario? By choosing EHRs from reliable, stable companies fully dedicated to their products. If updates are extra-slow, for example, you should be a little worried. It suggests that the company is not truly invested in their EMR solution.

Assuming the employment of cloud technology and multiple backup systems, though, digital would win over paper. Paper records are often more difficult to copy, so a lot of medical record libraries have unique files without remote backups. This can spell certain disaster during accidents: fires, floods, termites, and the like.

The ID crises in New Orleans post-Katrina illustrate the problems that can arise when valuable paper records become nigh-on unrecoverable. Thousands of persons’ identity documents—including birth certificates—were washed away.

Regular flooding threatens paper record libraries in the Philippines.

Another concrete example of how EHRs can be more “durable” can be found in a 2013 incident in the US . That year, the Moore Medical Center in Oklahoma was devastated by a tornado that tore off the hospital’s roof and crumbled its walls.

Miraculously, there were no fatalities following the incident. Furthermore, the hospital’s use of an EHR tied into the city’s health information exchange allowed transfer hospitals to basically pick up where Moore Medical’s professionals left off. Had the hospital still been using paper documentation, most of the patients’ records might have been destroyed—either damaged by the rain or blown away.

The short answer: Digital wins.

The long answer: Digital health records are often more complete than paper ones. Part of it might be due to the facilitation of organization and retrieval. It might also be due to many EHRs offering patient portals allowing the subjects of records to fill in their own data at leisure. Whatever the case, research regularly shows digital records being more complete.

In a study on the use of digital health records in a mental health institution, for example, EMRs were found to be 40% more complete than their paper counterparts. Another study, this one in Australian aged care facilities, found EHRs regularly logging higher completeness values for different medical forms. The biggest difference in completeness was found between the two for health history forms: 67% against 43%.

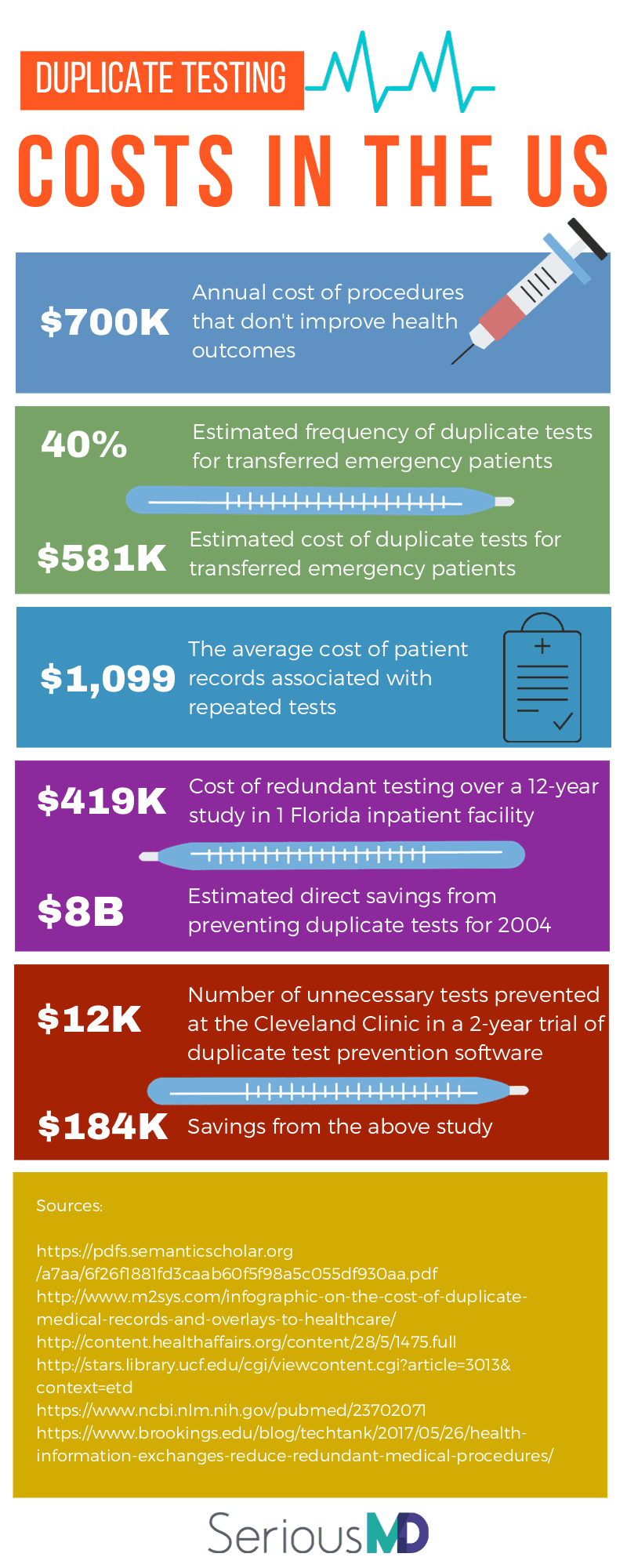

Master record duplication may be the darker side of the completeness issue in healthcare, though. Both paper and electronic medical record systems suffer from it.

The average record duplication rate in a hospital setting is 10%. The average added cost per duplicate record is $20. This can turn into thousands if that duplicate file leads to an adverse event.

Redundancy in a paper system has to be found and corrected manually, however. This can be very costly and time-intensive. By contrast, digital systems can also make use of supplementary technologies like probabilistic algorithms (50.8% use this), deterministic matches (34.4%), and biometric matching (5.5%).

The short answer: Digital wins… if you exclude the costs of conversion for massive record libraries.

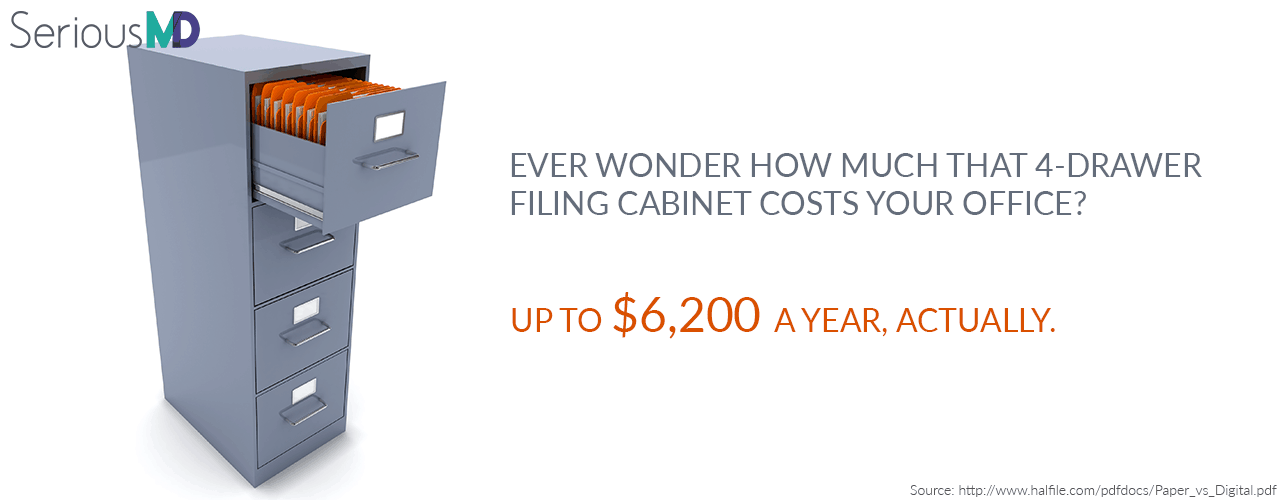

The long answer: The costs involved in paper records come from multiple sources. The first would be from their creation, which itself takes money. It is estimated that each healthcare worker incurs anywhere from $850 to $1,000 in document printing costs per annum, for example.

Then there are the costs of storing these documents. In some countries, these are even higher because of regulations obliging them to store patient records for certain periods of time after their creation. In the US, for instance, 6,000 hospitals spend around $10 billion per year just to archive patient records.

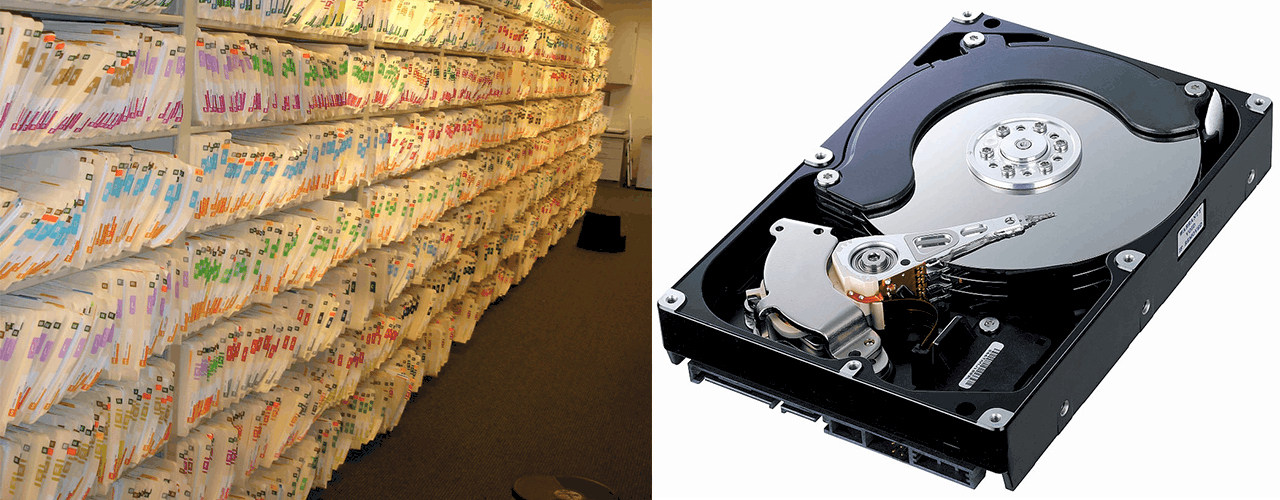

Paper records require more physical space than digital ones. The shelves on the left could fit several hundred of the hard drives on the right.

The costs for storing data in the digital format are very low when compared to those for paper. This is true not just for medical records but for other documents.

In a review of book storage costs, for instance, paper cost around $5.89 a year while digital cost around $0.10. A report mentioned in the same review also stated that paper storage costs rise 4% each year while digital costs drop by 50% every 5 years.

There is obviously a big gap in price tags between the two media. Inherent to storage costs for physical (paper) records too is the cost of maintenance. One 4-drawer file cabinet can cost as much as $6,200 a year to fill and maintain.

A 1TB hard drive capable of holding all the information (and more!) in that file cabinet would cost just a little over $50—and computers could be used to handle most of the maintenance.

The Center for Information Technology Leadership estimates that a switch from paper to EMRs would save US healthcare providers $44 billion a year. Everything from printing costs to disposal expenses (because medical records have to be disposed of securely, to avoid privacy breaches) goes into this, presenting a strong argument for digital documents.

But there is a hitch that might prevent—or at least, strongly delay—digitization for some healthcare organizations. This is the cost of conversion.

The cost of converting existing paper records to digital ones is considerable. It would be more manageable for smaller clinics or independent practices. This is because they would have fewer records to convert.

Patient medical records still kept on paper at the Chinatown Public Health Clinic. Photo by Jason Winshell,SF Public Press.

For the large hospitals, though, a staggering amount of labor and time is involved. The price tag can get shockingly high when a lot of historical records are concerned—for a hospital like Johns Hopkins, for instance, it can reach an estimated cost of $1 billion.

A big part of the cost comes from preparation. One expert estimated that for every hour his team spent on scanning documents, another 4 or 5 hours would be spent on prep alone.

Paper records have to be re-examined for quality and re-indexed before being converted. Now think about the hundreds of thousands of records some hospitals have and you see where costs could skyrocket. Digital records might still see more savings in the long run, though. The outlay for converting is simply bigger.

The short answer: Theoretically, Digital is better. Practically, it depends.

The long answer: This is a thorny one. Most discuss efficiency purely from the aspect of time, specifically time spent charting vs. interacting with patients.

It appears to make sense at first. Most healthcare professionals spend more time on documentation than actual patient contact, which has long been a concern. With a measly 30-40 hours spent on direct patient interaction, time gains that can be added to those would thus seem to be a good marker of EHR efficiency.

Yet this must be pointed out: it would hardly be reasonable if gains made in time are at the expense of care. Surely no physician would consider his practice having gained in efficiency if he managed to shorten charting hours while increasing negative patient outcomes?

That said, let us assume for the moment that time efficiency is our key concern. Does Paper or Digital win?

Theoretically, the latter would. Digital data entry, processing, and retrieval has possibilities unmatched by paper. Consider the following sticking points for paper records, which would reduce time efficiency:

Paper records involve onerous organizational requirements that eat into time efficiency.

Relative to #1, more adaptable and techno-savvy users will likely find it easier to switch. It is not unlikely that this would lead to more capable usage more quickly, which could lead to time efficiency gains. Better support and training from management or the EHR vendor (#4) help too.

In the same way, flexibility and user-friendliness of design go a long way to helping people use a program to their advantage. Consider #2.

The more divergent an EHR is from the traditional paper system, the more time it could take to switch to it. Personnel will have to break from previous habits and paths of behavior, after all.

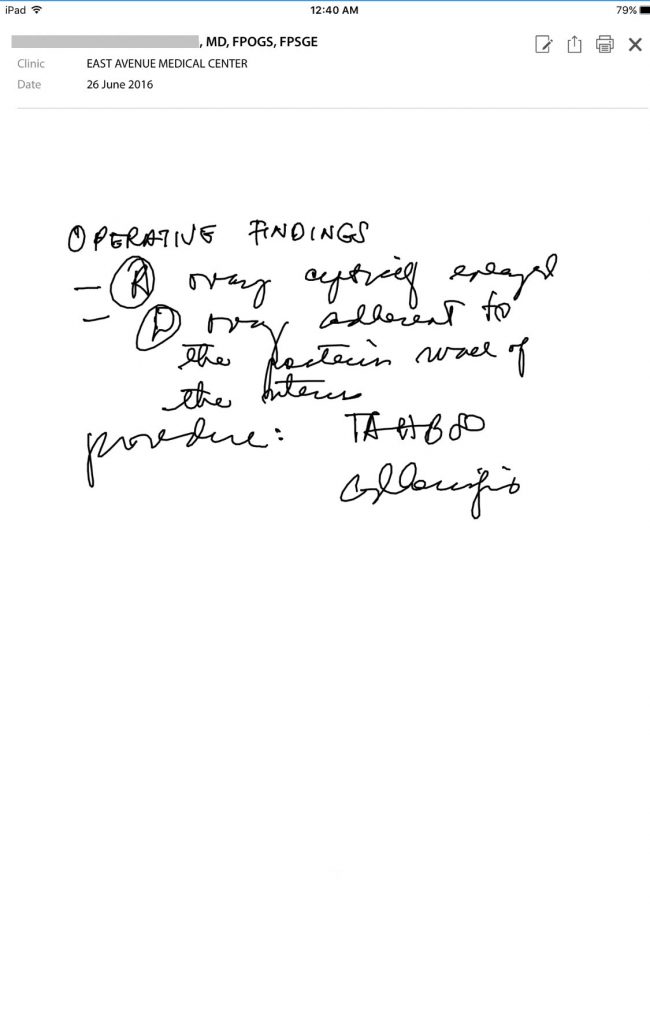

This might sound insurmountable in the matter of switching from paper to digital. Yet, some EHRs permit data entry that approximates the traditional method. For example, SeriousMD allows users to scribble notes directly on their devices as in conventional paper note-taking. This may mean quicker uptake for less techno-savvy users.

SeriousMD users can scribble "handwritten" notes directly onto their touchscreens.

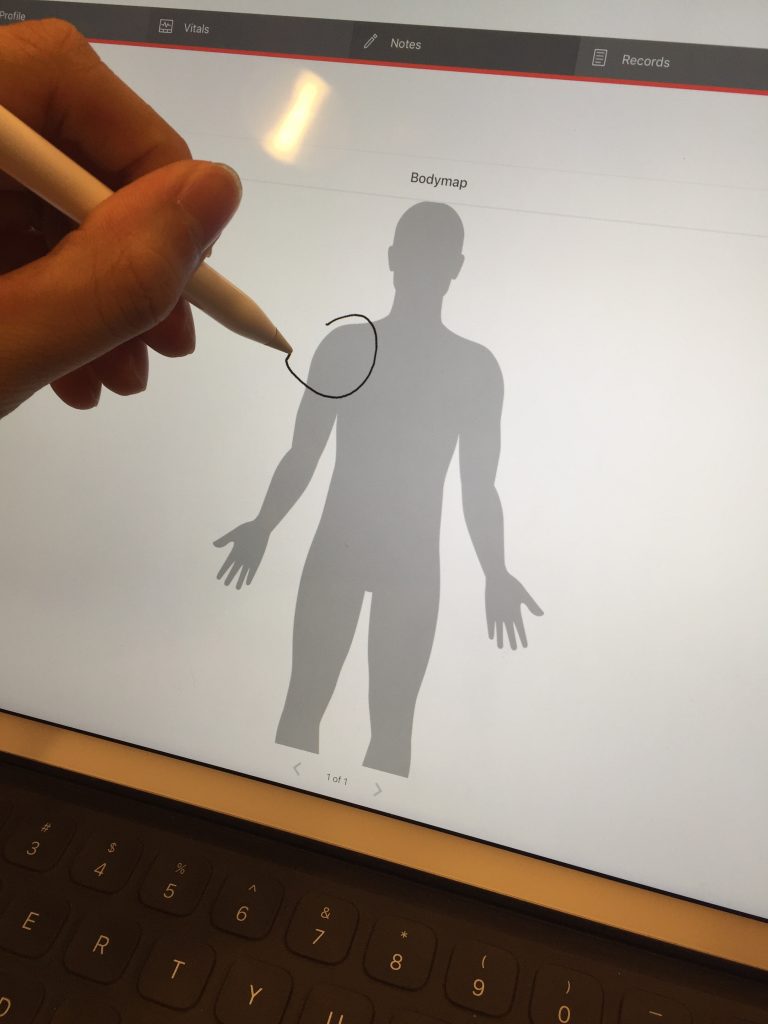

SeriousMD users can also scribble notes on a body chart.

Would that still mean time efficiency gains? Possibly, though not certainly.

Even more interesting, perhaps, is that some factors here might not lead to the results one would expect. Let us look into #5 from our list: the time elapsed since implementation.

Most people would suppose that time efficiency goes up the longer an EHR has been in use at a practice. After all, that means people would have had more time to get used to it. It only makes sense that they would be faster then.

The data seems to say otherwise.

A systematic review of studies about EHR impact on time efficiency was published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. In it, researchers discovered what seemed to be a negative correlation between the amount of time elapsed after EHR implementation and time efficiency.

Simply put, when physicians were evaluated 3 months or less after EHR implementation, researchers found them spending less time on documentation. Yet when physicians were evaluated more than 3 months after EHR implementation, researchers found them spending more.

Does this mean time efficiency drops the longer you use digital documentation? As the authors of the review noted, a more probable explanation might be that users were discovering new functionalities of the EHR after 3 months of use. As they were adding these new functions to the ones they regularly used, it would explain the longer documentation times.

If this is true, it would be hasty to say this suggests how EMR software produces inefficiency—especially as it might propose that users’ documentation had become more robust, benefiting patients.

This points to a better definition of efficiency than is commonly used in the topic. Perhaps efficiency should be better thought of as organizational efficiency when it comes to medical documentation.

Time efficiency remains a big part of it, yes. Yet, so should patient outcomes and overall efficiency (e.g. time spent on point-of-care documentation may increase while that spent on data lookup or cross-checking decreases).

At any rate, while Digital does have striking potential to outdo Paper here, that potential cannot be realized without effective implementation and support. Implementation officers need to pay close attention to their circumstances.

The review mentioned earlier, for example, noted that nurses were actually more likely to see time efficiency gains from EHRs than physicians. A potential cause was the difference in data being taken down.

Nurses using EHR bedside terminals also saved more time than those who used central stations (24.5% vs. 23.5%), according to the review.

Most nurses take information meant for standardized forms. On the other hand, doctors are less likely to work with standardized templates. Naturally, template-friendly EHRs would be more nurse-friendly than physician-friendly too.

This suggests that EHR implementation for physicians might have to take a slightly different route to reflect similar time efficiency benefits as those for nurses. Or, at least, that EHR vendors need to look into this matter further.

EHRs are unlikely to go away, so more and more healthcare workers will have to learn to make their peace with this still-evolving technology. Paper record-keeping methods have the advantages of long use and tweaking over the years. For people to see similar advantages from digital methods, they should be willing to tweak their implementation when needed . Otherwise, Digital’s theoretical benefits may never become practical realities.

The short answer: Digital wins.

The long answer: Organization is far easier when you have computers to do most of the work (like sorting, indexing, etc.) for you. The physical challenges of organizing a large library too—storage space, partitions, etc.—vanish with digital documents.

Imagine organizing patient file libraries like this one (from Surrey and Sussex), which have over 200,000 files.

Paper filing systems are actually susceptible to high rates of document loss. The many steps and distances that have to be covered, along with human error in the organization process, contribute to the numbers. One study even estimated that as many as 7.5% of paper documents end up lost. Another 3% end up being misfiled.

There are actually hybrid systems supplementing paper with digital organization tech, though. Usually, it is done prior to the practice’s full digitization of its records.

A good example is the Intelligent File and Inventory Tracking solution in several NHS hospitals in the UK. It uses RFID tags and scanners to make tracking, filing, and organizing paper records easier.

A handheld scanner used for reading RFID tags at an NHS patient records facility.

The critical point to make is that such solutions remain interim ones. Hospital administrators from the NHS agree that the true solution is still to digitize all their records for the future. But given the massive size of some hospitals’ record libraries, that may take some time.

The short answer: Digital wins.

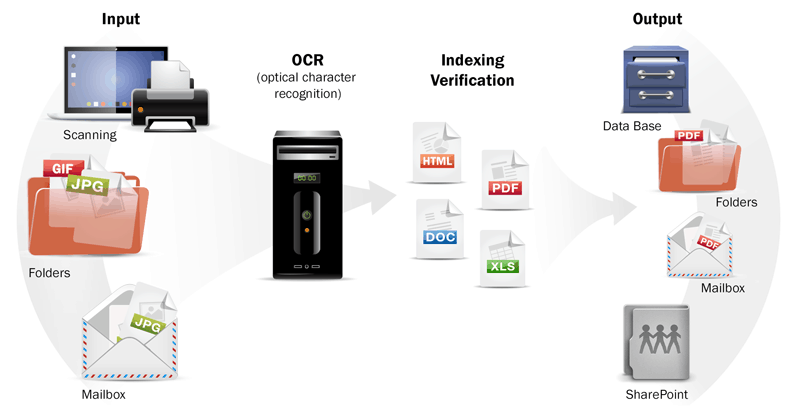

The long answer: This is one of the areas where digital documents undeniably outstrip paper. OCR or optical character recognition technology can render a newly-scanned document fully searchable in a flash. Simple automatic searches make data lookup near-instantaneous.

In fact, a 2007 comparison showed EHRs being 20% faster than paper when it came to data search and retrieval. With computer processing getting better as time goes on, there is little reason to suppose the situation would reverse now.

An explanation of OCR technology - image by Wisetrend.

For paper records to even approach the same degree of searchability, there has to be a rigorous indexing system in place. The mere creation, never mind the maintenance of such a system can eat drastically into labor hours.

Most hospitals and large practices even find themselves having to hire a specific employee or several to fulfil that function. That would be yet another cost for the practice involved. And even with 4 or so persons assigned to the task, it would still fail to match the speed of digital search.

A final thing of note is that digital searches can be performed and fulfilled from a single terminal (a computer). There is no need for the person to travel from one location to another in situations where the paper record is kept off-site.

The short answer: Assuming the latest in digital security measures, Digital tends to be safer. Even without those measures, though, there is no guarantee that Paper would be more secure. It would still depend on the regulations for access at a particular facility.

The long answer: Both paper and digital documents have vulnerabilities. Both have possibilities for securing them against prying eyes, including organizational rules of access, locked storage (password protection for digital), and monitoring.

Digital does have advantages unique to it, though. Perhaps the most important one here is the audit log. This is a record of who accessed a patient file or made alterations to it throughout its history. The best audit logs are non-editable and always operational, making fraud/tampering sans detection challenging.

Digital documents can also be encrypted for safety. This is not something you can generally do with paper medical records, as they need to be permanently legible.

So why all the ongoing fears about digital records’ vulnerability? We have already discussed this in our article on the Pros and Cons of EHRs (see the Security tab of that piece). Basically, most of the dangers come from vendors rushing to offer software that does not fulfil minimum security regulations. Were you to actually use an EHR fulfilling all the security requirements, though, your data would likely be safer than if it had been in your filing cabinet.

The short answer: Digital wins, but with a caveat.

The long answer: Digital documents are more easily shared than paper ones as they can be sent wirelessly. Paper records have to be faxed or printed, copied, and then transported. All of that incurs time, expense, and labor. In fact, the challenge of sharing paper records is the chief reason patients spend so much on duplicate tests per year (in the US, up to $20 billion a year).

By contrast, you could simply send a digital image of a test result to someone via email. The physician would no longer have to wait for a courier and the patient would no longer have to spend money on copies or even duplicate tests.

So what is the caveat here? That while digital documentation is very easily shared with others using certain technologies (cloud uploads and syncing, email attachments, etc.), it can be less so with some program-to-program matchups.

To be exact, a lot of EHRs are not yet interoperable. This means that most EHR programs will actually be unable to send a patient file directly to each other. Why? Because the way they store and use data is often different.

Of course, the obvious workaround is to create another digital document in a widely-accessible format. Think of a PDF or PDF/A version of a chart, for example, or a PNG snapshot of the file as an image. You can then send that to someone using other channels like email.

Health information exchanges could help bridge the gap too. They have already been touted as part of the solution for reducing issues like duplicate testing.

Still, the ultimate goal remains for EHRs to become interoperable. This would require creation of industry-wide standards and regulations on electronic medical data, however. The industry is still a way off from that.

So while Paper still does have its virtues, Digital (while it may still be a work in progress) is undeniably the future.

Do you agree or disagree? Tell us why here or on social media (Twitter/Facebook)!

Or, if you just want to find out what a digital medical record system can do for you, get in touch with us and we’ll give you a call back to answer all your questions! This might help you decide if it’s finally time to move your practice into Philippine healthcare’s future.